|

|

|

| | Home | People behind the Scenes | Richard Emmert |

| |

|

|

|

Photo: Shigeyoshi Ohi |

When visiting the National Noh Theatre, one often sees foreigners in the audience. There are many foreigners interested in seeing a performance of Noh as part of the traditional culture of Japan. But it is quite rare for foreigners to fall in love with Noh, so much so that they study it and learn to perform its chant and dance. And there are only a handful among those who have studied Noh to the extent that they in turn become committed to teaching it to others.

Richard Emmert, born in Ohio in the United States, is one of them. He came to Japan over 40 years ago to study Japanese traditional music, and though he planned to return home after two years, by chance he began taking lessons in Noh and gradually began to study the various aspects of its performance including its dance, chant and four hayashi instruments.

Professor Emmert teaches Asian and traditional Japanese performing arts in the Faculty of Literature at Musashino University in Tokyo, but he is also involved in conducting practical Noh workshops both in Japan and abroad through which he has taught many foreigners and Japanese alike. He is the founder and artistic director of the theatre company Theatre Nohgaku, based in Japan and the US, which has as its key mission the performance of new and classical Noh plays in English.

Professor Emmert spends every day with Noh, always continuing to study, teach and practice it in even greater depth. He shared with us his thoughts and memories from his first involvement with Noh until the present.

Laughing on First Hearing Noh

-- (Editing department) What made you want to begin studying Noh?

Emmert: I first encountered Noh while at college. I was born in Ohio and went to Earlham College in neighbouring Indiana, where I studied Japanese history as well as theatre and music. I took a seminar on Noh there.

-- There was a course on Noh? That’s rare.

Emmert: Earlham is a small school, but they have a long relationship with Waseda University and have long had a number of courses on Japan. One special seminar during my sophomore year was on Noh and taught jointly by a theatre professor and a music professor. These two professors had both studied in Japan, and had seen many Noh performances. Since I was planning to study abroad at Waseda University the following year, one of my best friends told me about the Noh seminar and convinced me to take it.

In the first class, the music professor put on a record of Noh music. When we heard the drum calls of the hayashi instruments, my friend and I could hardly keep from laughing—we had never heard music like that before. We tried very hard not to laugh as it seemed like everyone else in the class was sitting there listening to it quite seriously. So my first impression of Noh was that the music was incredibly strange and my reaction was to laugh.

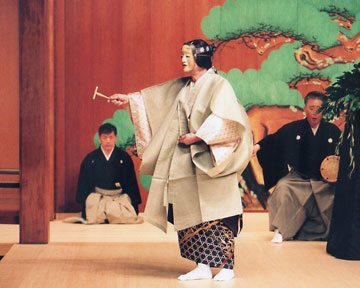

Playing the Shite in the English Noh St. Francis

|

Photo: Shigeyoshi Ohi |

In that seminar, we studied various things about Noh, but the class was mainly to prepare to perform a play St. Francis, that the theatre professor, Arthur Little, had written, and for which the music professor, Leonard Holvik, had composed music. Both the text and the music took much from noh conventions and we called it an English noh play. Somehow I was chosen to take the shite lead role in the production.

-- That’s interesting.

Emmert: The performance was a success and later, with the support of the Ford Foundation, a film of the play was also made. So even though I had the lead role, it didn’t necessarily mean that I wanted to jump right in and study traditional Noh once I came to Japan.

So after that, in the summer of 1970, I came to Japan in a year abroad program and began to study at Waseda. There I had the opportunity to take a class with Japan’s most famous ethnomusicologist, Professor Fumio Koizumi of Tokyo University of the Arts, who also was teaching part-time at Waseda about traditional Japanese music. I wanted to study a traditional musical instrument during my year in Japan, so he introduced me to a shakuhachi teacher, Yamaguchi Goro, with whom I began taking lessons. After the year in Japan I returned to America and graduated from Earlham, but then decided to come back for a second time which I did in June of 1973. I planned to stay this second time for two years, but in fact, plans changed and I have been based in Japan ever since.

Studying at Tokyo Geidai and Entering the World of Noh

-- What did you do when you returned to Japan?

Emmert: I began taking lessons in Noh in November 1973 after a chance encounter. I saw an announcement in the newspaper about a special screening of our film, St. Francis , so I went to it. Don Kenny, who studied kyōgen with the great kyogen actor, Mansaku Nomura, spoke at the screening, and when we talked afterwards, he told me how he wanted to produce St. Francis in Tokyo and asked me to direct the music. I suggested that if I was going to do that, I should study Noh, so he introduced me to Akira Matsui, a young professional Noh actor of the Kita School, with whom I began taking lessons in Noh dance and chant. And eventually in 1975, I helped Don put up performances of St. Francis in Tokyo with Matsui sensei also helping us.

Also, with the help of Professor Koizumi, I was accepted into the Department of Musicology at Tokyo University of the Arts (Geidai) in April 1974. I became a research student my first year and entered the regular graduate program in my second year.

-- Why did you go right to Noh from there?

Emmert: I didn’t actually do much Noh my first year. Instead, I took various classes on Asian and Japanese traditional music, including Professor Mario Yokomichi’s lectures on Noh. Since I was already taking lessons in the chant and dance of Noh, his class was particularly interesting and useful and after that I sat in on all his classes as long as I was at Geidai.

From my second year at Geidai, however, I decided to take lessons in the hayashi instruments of Noh, and began by studying Isso school flute with Yukimasa Isso and Ko school drums with Akihiro Sumikoma. Two years later, I began learning Takayasu school ōtsuzumi from Takashi Kakihara and Konparu School taiko from Gentaro Mishima.

-- So you really studied all of the hayashi!

Emmert: Yes. Since I was still learning the shakuhachi at the time, every day was practice, practice, practice. Though I was a student at Geidai, I was mainly taking performance lessons in noh and shakuhachi and just a few classes at Geidai in between (laughing). There were Noh performance classes at Geidai too, but one of my Geidai friends who studied noh suggested that private lessons outside the university would be more intense, and so I ended up studying privately with several different Noh teachers.

Getting Deeper Into Noh

-- So why did you become so passionate about Noh?

Emmert: My Japanese speaking ability was getting better, and also as I took more lessons in noh, they fed off each other and became more and more interesting. My teachers were always very serious about teaching me. I had studied a lot of music when I was young, singing in choirs, and learning clarinet and guitar, and I also was always interested in theatre. I also played a lot of sports when I was young and liked being active. As a side story, when I did the role of the shite in St. Francis at college, Eleanor King, a famous modern dancer, choreographed my movement. She had come to Japan in the 50s to study Japanese dance, and saw a lot of Noh while she was here. She actually asked me if I was interested in studying modern dance so I seemed to have some movement talent.

While there are many people both in Japan and abroad who become interested in Noh from a literary standpoint, my interest was really in terms of performance. It started with an interest in the movement and music. From there, I gradually began to understand more about the beauty of the text as literature. But I did not start by trying to understand the meaning of Noh stories. And because of that, I was able to simply enjoy Noh by taking lessons and watching performances even though I often didn’t really know the story of what I was doing or seeing.

Researching Noh and Teaching at a Japanese University

|

Professor Emmert at home wearing a samue, the traditional working clothes of a Japanese Zen monk. Behind him are pieces of traditional Asian artwork, another of his areas of expertise.

Photo: Shigeyoshi Ohi |

-- What kind of research did you do in graduate school?

Emmert: I wanted to study the music of Noh, and wrote my master’s thesis on the musical aspects of the chû-no-mai dance. In the doctoral program I studied the differences between the various schools of Noh. I joined Musashino University as an assistant in the Noh Research Archives in 1983, then went on to become an assistant professor in 1986, and later an associate professor and finally full professor.

The Lasting Attraction of Noh

-- Looking back on your years of studying Noh, what do you find to be the most fascinating thing about it?

Emmert: I began to study Noh knowing very little about it, but over time I became fascinated with its energy and power. For people who think Noh is just quiet, that seems a contradiction. You feel a lot of energy, whether watching others perform or performing yourself. Even when playing the role of a graceful woman in a quiet play, you feel a deep and quiet energy within you. This intense energy must be constantly maintained and controlled for the chant, dance and hayashi. To perform a full Noh, sustained energy is required. And this energy is not random bursts, but is controlled and negotiated as a means of expression.

I also have come to feel over the past few years the importance of Noh as a journey.

-- In what way?

Emmert: First, the waki sets out on a journey and arrives at the place of the story. When you think of how that place exists, its past, its present or its future, I moved by what that can represent.

-- You feel like the place tells a story!

Emmert: It does and perhaps Noh stories can be told in different places. For example, a Noh story might be possible in the place we are now. What happened here 50 years ago, or 100 years ago, or what will happen in 50 years, or 100 years. Noh makes you think about the significance of the places we inhabit, and the fact that we occupy these places for a short time but they have been occupied by others before and will be occupied by yet others in the future.

Noh is an interesting means to have an imaginary conversation with people from the past. How can ghosts from the past resolve issues they had in life? Many different stories are possible using the medium of Noh and its concern with place and spirits from that place. That is what makes it so fascinating.

Performing Noh Plays

-- Which Noh plays do you like?

Emmert: I like a number of plays and have performed parts of many plays. I have performed the lead role in seven complete plays: Kumasaka, Kurozuka, Fujito, Momijigari, Kantan, Kiyotsune and Sumidagawa. I liked all of them. There are other plays too which I haven’t performed, but I also like, such as Atsumori. The special relationship between the waki and shite gives the Atsumori story a particularly emotional depth. I also like vibrant plays like Takasago. There are many plays that are interesting to explore and begin to feel how they can be performed.

Contemporary Noh in Modern Japanese

|

Richard Emmert performing the role of the shite in Sumidagawa at the Kita Noh Theatre in December 2007.

Photo: Kita School Photo Department Abiko Photos |

Emmert: In recent years, there have been an increasing number of new Noh plays performed, but I think there could be even more, especially more plays performed in modern Japanese. I like the classics and respect them immensely, but performing Noh using present-day Japanese language would be a step toward expanding Noh.

-- Does modern Japanese fit with Noh? Can it fit the music of Noh without sounding strange?

Emmert: Yes, I think it certainly can.

-- Perhaps, but I think it might be difficult.

Emmert: The world of Noh might think it is difficult.

-- That is also true, but won’t it be difficult to approach the level of performance which Noh has acquired over the years?

Emmert: That is true, but I think those kind of challenges are good.

-- It might seem strange at first, but it could develop into something sophisticated.

Emmert: Noh is built with formulaic expressions and structures. I think using the form of Noh with modern story elements could produce something quite interesting. It will likely take time for it to develop and be fully appreciated, but I think it would be a broadening of Noh’s appeal and it likely is a natural evolution of the art.

Sharing Noh with Foreigners

-- You teach Noh to foreigners through the Noh Training Project, Theatre Nohgaku and through many other workshop opportunities. What is hard about teaching foreigners Noh?

Emmert: In any kind of workshop, it’s often hard to pick what level to aim for. Some people know a little about Noh while others know nothing. Some people will become interested right away while others need more to be convinced, so it can be difficult adjusting to different levels in a short time. And even if they have already studied for awhile, if they haven’t had a chance to see much Noh, they sometimes make rather confusing assumptions. I generally teach classical Japanese Noh while I explain about the performance techniques in English, but of course not knowing any Japanese language is often difficult for foreigners in studying Noh.

-- What are you conscious of while teaching?

Emmert: I just try to plant the seeds that create interest in Noh. One never quite knows what people will do with what you teach them. Everyone has there own lives to lead and so I just try to make it interesting and enjoyable for those whom I teach and hope that some of them will do something meaningful with what they learn.

From English Noh to the Noh Training Project and Theatre Nohgaku

|

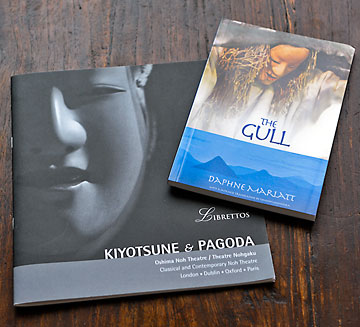

To the right, a pamphlet from the 2006 production of the English Noh play The Gull in Canada, and to the left a pamphlet from Kiyotsune & Pagoda, a production staged in Europe in 2009 jointly by Kita school members of the Oshima Noh Theatre and by Theatre Nohgaku. The Gull was written by Canadian poet Daphne Marlatt with music composed by Richard Emmert, and was the first English Noh play created in Canada. The 2009 tour included three countries and four cities, London, Dublin, Oxford and Paris. This was the first performance of the English Noh Pagoda.

Photo: Shigeyoshi Ohi |

|

In August 2009, a performance of Funabenkei was held for the 15th anniversary of the Noh Training Project in Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania. The photo is the cover of the anniversary video.

Photo: Shigeyoshi Ohi |

--Tell us about your activities with the Noh Training Project and Theatre Nohgaku

Emmert: In the 80s I began to have opportunities to compose and direct Noh plays in English. At that time I worked on productions of At the Hawk’s Well, Drifting Fires, St. Francis and Eliza. With English Noh plays, when we chose foreigners to sing they could sing but most had no training in chanting Noh style. When we chose Japanese performers who had Noh experience, they usually could not pronounce the English very well. Neither situation was very satisfactory so I began to feel that it was first necessary to teach foreigners basic techniques.

With that in mind, I started the Noh Training Project in Tokyo in 1991, teaching resident foreigners the dance and chant using excerpts from classical Noh plays in Japanese. Then in 1995 in the US, we started an intensive three-week summer program in Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania. As the program grew, we invited others to teach including my first teacher, Akira Matsui, as well as Mitsuo Kama as a Noh drum teacher, and Kinue Oshima, the only female professional in the Kita school.

Emmert: As the program grew, I began to reconsider why I had started the Noh Training Project in the first place—which was to train foreigners to do Noh in English. So in 2000, I invited some of my more experienced students as well as an old friend David Crandall and his wife Yukie, who had both been uchideshi disciples in the Hosho School, to rehearse At the Hawk’s Well, and as a result we formed Theatre Nohgaku. We had our first tour in the US in 2002.

-- I hear that you have done both the classics and English Noh.

Emmert: Members of Theatre Nohgaku (TN) were the principal performers of the classical Noh play Kurozuka in 2004, which we did in Japanese for the 10th anniversary performance of the Noh Training Project (NTP) in Bloomsburg. Then in 2006 we toured in the US another new English noh, Pine Barrens, written by Greg Giovanni of TN, then Crazy Jane by David Crandall in 2007, then another classical Noh in Japanese, Funabenkei, for the 15th anniversary of NTP in 2009. Finally, in December 2009, we toured both the classical Noh Kiyotsune along with a new English Noh by Jannette Cheong, Pagoda, in London, Dublin, Oxford and Paris along with the Oshima Noh Theatre of Fukuyama and with the support of the Agency for Cultural Affairs. We are planning to perform that in Japan and China in June and July of 2011.

-- How do the members of Theatre Nohgaku approach Noh?

Emmert: I think our goal is to perform with the energy and feeling of classical Noh. Of course, many of our members have much more experience doing Western theatre. And it takes time to grasp the subtle differences between performing Noh and performing Western theatre, and it is even more difficult to understand that difference given that many of our members have not spent much time in Japan. But still our focus is on performing English Noh in classical Noh style.

-- What is the goal of studying Noh so deeply?

Emmert: We are just aiming to get as close as possible to the level and abilities of professional Noh actors of the Japanese Noh world. We don’t just want to do a watered-down version of Noh. We still need to improve as a company and we understand that we cannot overnight reach the level of classical Noh in Japan. Still, we are trying to take the same serious approach to performing Noh as professionals take in Japan.

Less is More

--How do you share the special aspects of Noh with foreigners unfamiliar with it?

Emmert: I try and communicate the beauty of these special aspects by demonstrating them and talking about them. For example, I think the kakegoe drum calls are extremely interesting musically. So I demonstrate the kakegoe, and try and show their vibrancy and energy. I also talk about how energy of the drum calls as well as the chant and the positioning of the body with the basic posture enlivens the performance space, and I have talked about how that basic posture is different from, say, that of ballet.

Another thing I often mention is how Noh tends to cut out anything extraneous.

-- Cutting away the extraneous?

Emmert: The phrase “Less is More” is often used in the West to describe aspects of Japanese culture. The phrase doesn’t seem to have a comparable expression in Japanese, but it really makes sense. It is particularly profound in regards to Noh.

-- How do you feel about how Japanese people now approach Noh?

Emmert: There are of course many Japanese who know nothing about Noh. But there are probably more people seeing Noh now than ever before. Still with very little emphasis on Japanese traditional culture in the education system, many Japanese have begun to see Noh and other traditional theatre or music as something completely outside their experience and their understanding.

And for that reason, it really is unfortunate that Noh and other aspects of Japanese traditional culture are rarely taught in Japanese schools. While it is admirable that Western music and art is taught in schools, it would be better still if traditional music, art and performing arts were taken as seriously in the Japanese educational system as the arts of the West are.

Professor Emmert told us with a laugh: “I became so involved in Noh that I have never married. It almost seems like I married Noh instead. If I had a family, I might not have been able to study Noh to the degree I have.” For Professor Emmert, Noh is truly the most important part of his life. (Interview: June 14, 2010)

Profile : Richard Emmert

Richard Emmert is the founder and artistic director of Theatre Nohgaku, a theatre company dedicated to performing Noh in English. He is a professor at Musashino University in Tokyo, and a licensed instructor in Noh dance of the Kita School. Born in 1949 in Ohio, he entered Earlham College in 1968. He came to Japan in 1970 and studied at the International Division of Waseda University where he developed an interest in traditional Japanese music and theatre. After graduating from Earlham in 1972, he returned to Japan in 1973 and began taking lessons in Noh. The following year he began to study traditional Japanese and Asian performance at Tokyo University of the Arts, where he earned a master’s degree and completed course work on a doctoral degree. In addition to classical Noh performances, Professor Emmert has been involved in numerous productions and performances of English Noh, and released the CD Noh in English in 1990. He actively conducts workshops, lectures and speaks in Japan and abroad, and directs the Noh Training Project in Tokyo and Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania.

| Terms of Use | Contact Us | Link to us |

Copyright©

2026

the-NOH.com All right reserved.