Interview

Interview

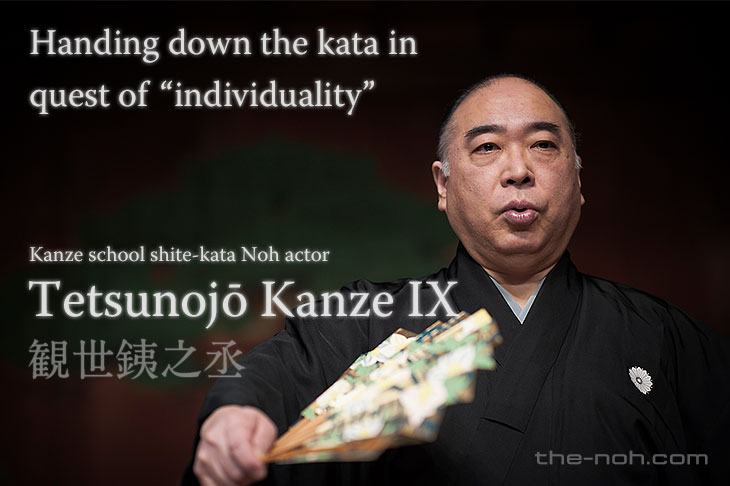

The following is a transcription of an interview with Kanze school shite-kata Noh actor Tetsunojō Kanze IX conducted by Kinue Oshima, a Noh actor of the Kita school.

In early April this year (2017), I paid a call on Tetsunojō Kanze IX at a training institute in Aoyama.

The Tetsunojō Kanze family has its origins in the Edo era (1603-1868), when it split from the Kanze Sōke (the leading family of the Kanze school). I was nervous ahead of our meeting, but its ninth-generation master greeted me with the softest of smiles.

Tetsunojō Kanze IX is a genial man with an amiable way of speaking and a mischievous side that emerges through the intermittent jokes he weaves into our conversation in such a way as to break the tension. In between occasional demonstrations of utai (vocals), Kanze spoke of the conflicting emotions he experienced over inheriting his family’s art, his unique theory of Noh drama, and numerous other topics. (September 21, 2017)

![]() Part 1: An emotional conflict that led to new perceptions

Part 1: An emotional conflict that led to new perceptions

![]() Part 2: A desire to convince audiences both at home and abroad of the allure of Noh

Part 2: A desire to convince audiences both at home and abroad of the allure of Noh

Interviewer: Kinue Oshima (Noh actor of the Kita school)

Photos: Ohi Shigeyoshi

Part 1: An emotional conflict that led to new perceptions

The Noh theatre company, Tessenkai

Oshima: One of the purposes of The Noh.com is to give people who have no knowledge of the world of Noh an appreciation of what it is that makes Noh so appealing and interesting to audiences, so I’ll be asking my questions today from the perspective of a newcomer to Noh.I’d like to ask you first to tell me a little about Tessenkai, the Noh theatre company you preside over.

Kanze: Of course. Tessenkai Theatre Company was founded almost one hundred years ago. It wasn’t until the Meiji era (1868-1912) that the first Noh ensembles to play before a public audience finally began to come together, and in those early days (at the beginning of the Taisho era of 1912-26), the performances were primarily given to groups of spectators who were practicing Noh as amateur apprentices. Because many of those scheduled performances were this way, the clear-cut distinctions between specialist and amateur performances that exist today are unlikely to have existed and the performances would have served as an extension of Noh practice.

The Tetsunojō Kanze family has had an extended family relationship with the Umekawa family since the time of the Meiji Restoration (1868), and we trained together. As is written in the Umekawa Jitsunikki (Diaries of Umekaka) and other documents, there was a period when our family was essentially a part of the Umekawa clan. Specifically, the Umekawa tradition of “ichi-roku no keiko” – practice sessions held on days featuring a “one” and a “six” (so the 1st and the 6th, and so forth) was one that our family adhered to. The fifth, sixth and seventh generation masters of the Tetsunojō family were raised in that tradition. The Tetsunojō and Umekawa families subsequently parted ways and our family took to holding morning practice sessions once a week. In consequence, I’m not sure when our inaugural performance was first staged, but I know that we began playing to audiences close to one hundred years ago.

Oshima: That’s an impressive length of time to have been giving public performances.

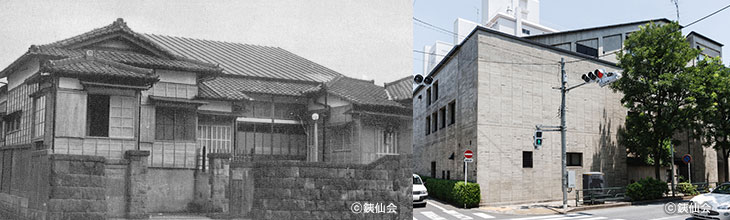

Kanze: As I understand it, “Tessenkai”, a portmanteau word that was formed from the names of two individuals: the “Tetsu” in Tetsunojō and the Noh flutist, Senji Isso, who was a relative and a member of family practice sessions and who is also an ancestor of present-day Hisayuki, began life as a practice meeting for Noh professionals. Another version of the story has it that a small sword bestowed upon the family by the Shogun had the characters for “Tessen” (Clematis chinensis or Chinese clematis) imprinted on it and that the family changed the characters to create “Tessenkai”, but it is impossible to know whether that story is true or not. It might be possible to verify the tale if the sword were still in existence, but it is thought to have been destroyed either during the war or by the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. Up until 1980, this stage was housed in a wooden single-story building.

Oshima: I imagine the voices of apprentices practicing utai (vocals) must have reverberated through the neighborhood back then.

Kanze: During the summer months there were training sessions that started at seven in the morning. The windows were wide open and one day an irate voice came from someone holding a baby next-door: “I have no idea what you people are doing with flutes and drums first thing in the morning, but do something about it!” (laughs). Thereafter, the shutters were kept closed even in the height of summer and the practice sessions pushed back a little so that they commenced at eight o’clock.

Oshima: Is that why the theatre was rebuilt using concrete?

Kanze: Yes, though that didn’t happen until many years later.

A short walk from Omotesando Crossing, the Tessenkai Theatre nestles on a corner at the end of a string of luxury brand stores that line Miyuki-dori Avenue. Rebuilt in 1980, it now has a truly modern appearance.

Born into a branch of the Kanze Sōke

Oshima: I first had the honor of seeing the Aoyama Noh plays and regularly scheduled performances of the Tessenkai Theatre ensemble when I was a student and the freshness of these performances, so different from the Kita school tradition in which I’d been raised, impressed me.

Would you mind sharing with us something of what it was like to be raised as a child of a branch of the Kanze Sōke (the leading family of the Kanze school)?

Kanze: As you know, we begin lessons in shimai (dance) and other aspects of the art of Noh from an early age. The children of Noh families are not only given child roles to perform, but also appear as spirits and gods and other parts of that nature. Similarly, the role of the master Yoshitsune in Funa-Benkei (“Benkei in a Boat”; see the Noh Plays database) and Ataka (see the Noh Plays database), which is traditionally played by an adult actor, is sometimes played by a ko-kata (juvenile actor) because it creates a good contrast between the cast members on stage.

Those early lessons were truly a world of sticks and carrots. Do my best and I’d win praise and a reward for good work, which of course made me happy. Perform badly and my father (Tetsunojō Kanze VIII; real name Shizuo Kanze) would scold me roundly; I was terrified of him then. He was genuinely frightening: I’d recoil in fear when he raised his hand and admonished me from above in his classically trained voice and those moments of being paralyzed by fear when my father raised his thunderous voice at me continued well into his twilight years (laughs).

Whilst my father gave his utmost to my training, it didn’t make me want to be an active teacher of Noh. I hope this won’t sound disrespectful to you, but I grew up with an older and younger sister – no brothers – and so was never particularly competitive. I merely felt that my sisters were lucky to have the opportunity to walk away (which is not to disparage the daughters of Noh families, only to say that the pressure to inherit the family name inevitably falls on the sons).

Oshima: I suspect my younger brother (the Kita school shite-kata Noh actor, Teruhisa Oshima ) experienced similar emotions. I simply refused to give up.

Kanze: At any rate, I was extremely nonchalant about my training and my father was incredibly busy so he was unable to devote much time to me. We’d practice a play once and my father would say: “You’ve done it now, so you understand it, right?” He’d give me training if I told him I didn’t get it, but it was always with a great sigh of resignation.

Oshima: I know exactly what you mean.

Kanze: My father was one of four brothers: Hisao, Hideo and the third son, Yukio; he died at the age of ten or eleven, and then there was my father (Shizuo). My father was the youngest so he had many opportunities to watch his brothers train. As I understand it, he participated in these training sessions out of a desire to be included by his older brothers, and in consequence was able to grasp quite a bit with only a little practice. Moreover, my father loved Noh from an early age, but it wasn’t like that for me. When I was a child, sitting in the formal seiza position, with knees together, back straight and buttocks resting on ankles, was no longer a quintessential part of daily living, but my father would admonish me if my legs started to hurt and I moved. “Why are you moving?” he’d yell, but it hurts, doesn’t it?

Oshima: Even simply sitting in the seiza position is hard when you’re a child.

Kanze: Even so, I appeared on stage in a fair number of ko-kata (child) roles. My recitations were good when I was in good condition, but I was prone to sore throats and experienced considerable pressure if I was given a succession of ko-kata roles to play.

I was scolded by my father from an early age and so it was never possible for me to be careless in my recitations. I developed a habit of becoming frantic when I vocalized, whether that be in training or for a mōshi-awase(run-through rehearsal). It’s something I still struggle with today.

Speaking loudly on stage can destroy the world view the adult actors have created in an instant, and ko-kata (child actors) have the power to turn conditions on stage upside down, which was a pleasant sensation, even when I couldn’t really follow what was going on. So appearing on stage was frightening, but it was also mesmerizing experience.

I stopped being given ko-kata roles towards the end of my middle school years, which is when I began practicing adult roles. Adult characters are required to perform wearing masks and that changed everything for me.

This coincided with the most productive years of my father’s life, a time when he needed to devote all his time to his work, and he basically told me I was responsible for training myself, and for doing it properly.

Oshima: That’s the way it tends to go in families, is it not?

A youth spent in conflict

Kanze: From hayashi-kata (musical accompaniment) training sessions and jiutai (the Noh chorus), to the job of kōken (stage assistant), there are an enormous number of elements that you need to commit to memory. I worked with fierce desperation every day, but I had my schoolwork to do and invitations from friends, too. Which inevitably meant that there were parts I’d failed to memorize by the day of a performance. If I was appearing as part of the jiutai chorus of performers, I’d listen to the voices of the performers behind me and simply intone a wavering version of whatever they were chanting. Everyone else sang robustly from their diaphragms, my voice was weedy and merely followed the tune of the musical accompaniment and I was reprimanded sharply for being out of tune, which left me feeling wretched.

As an underling, I’d go backstage early to help with the preparations and do all the clearing up, but I was always being shouted at. Even when I folded the costumes, I’d be told off for my method of folding them; all I got was complaints. I enjoyed playing with my friends and going to my school clubs, but I didn’t study so my grades fell off and I was sent to a tutor. What with that and the need to practice the hayashi-kata (musician work), there really weren’t enough hours left in the day.

At this point in my life, I found myself asking whether I was really cut out for a life as a Noh performer. I believed I had no talent for it and was convinced it would be better if I simply quit. After all, my father and my uncle Hisao were stars of the Noh world. The people around me had the brightly shining eyes of characters in comic books for girls when they listened to talk of my father and uncle, and I’d see the skillfulness and wonder of their art, but I didn’t get any better no matter how hard I practiced and became obsessed with how “poor” my own performances were. I may not have known how to get any better, but I recognized poor art when I saw it. That’s why I found the gap between my ideals and the reality of my performances to be so intolerable and why there were days when I spent much of the time vowing that I didn’t care how severe the beating, I’d tell my father tomorrow of my decision to quit.

Oshima: I had no idea how hard you’d struggled.

Kanze: In my family, the role (of heir to the family’s art) could have fallen either to me or to my cousin, but my cousin decided to give up and so it was left to me to take over. I felt a responsibility towards continuing the family art and yet the feasibility of getting anywhere close to the world of my father and uncle felt very remote. I was convinced that it would make the people around me unhappy, that it would lead to my own unhappiness, and until I reached the age of majority I truly believed I would quit.

But everything changed on the sudden death of my uncle Hisao. Tessenkai is a small theatre company and it would be short of hands without its lead actor; at the very least I had to be ready for such a battle. I was 22, but my work increased thick and fast, with people calling on me to perform in that jiutai (chorus), as kōken (stage assistant) in that performance, to carry props, and so forth. And it fell to my father to stand in for my uncle Hisao. The roles performed by my uncle Hisao were all extremely intricate and since my father was a star in his own right, he too was working under intense pressure. He’d be up early every day for practice or a mōshi-awase (run-through rehearsal), and all performances were followed by a drinking session so he’d be out all night on those days. He’d nap afterwards, but by the time I’d left for school he’d done with his research and was off out again. I thought that lifestyle would be the end of him.

Oshima: Social relations become important when you reach the top of your profession, on top of all the other responsibilities you’re required to fulfill; I can only imagine how grueling that must be.

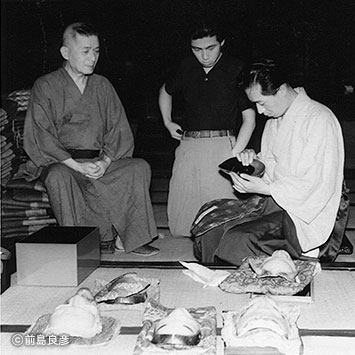

Tetsunojō VI, Kasetsu Kanze, seen giving the Noh masks a summer airing; with Hisao Kanze, who was Shizuo’s eldest brother, and uncle to Tetsunojō Kanze IX; and Shizuo Kanze - Tetsunojō VIII, and father of Tetsunojō Kanze IX.

Reminiscing about his father, Shizuo Kanze, and his uncle, Hisao Kanze, Tetsunojō Kanze IX would occasionally beam from ear to ear.

Kanze: There were times when both my father and my uncle (Hisao) disliked having to have students along with them and would go it alone. They’d carry their own cases and I felt that the least, the very least, I could do was to relieve them of the heavy items. I wasn’t yet earning my own bread and if my father collapsed, responsibility for the household would fall to me and I was powerless, so I began serving as my father’s dogsbody since I wanted to do everything I could to prolong his life, even if only for a day. Up to that point, I’d spent my days asking: “What are you so angry about? Why are you shouting at my mother for such unjust reasons?” Now, though, I found myself wondering what it was he actually wanted done, what it was that had happened to provoke my father into speaking that way. By accompanying my father as his man of all work I could see how he dealt with the people he encountered and gradually I became able to second-guess his reactions, to know what he would say before he opened his mouth. It was then that I began to understand the various processes and social obligations preceding each performance, to recognize that these performances went without hitch because there were people working hard behind the scenes to make those performances happen.

Oshima: The death of your uncle and your assuming the role of man of all work to your (esteemed) father based on a desire to assist him in his work, thus effectively gave you your first insight into the backstage workings of the Noh theatre, then.

Kanze: My fear of Noh also began to abate and I started to put everything I had into it. Until that point I’d thought only about my stage appearances and so, out of nowhere, I was comparing myself to my father and my uncle, which was quite wrongheaded. I’d become utterly dispirited. I convinced myself that I was “no match” for either man, no matter how hard I practiced. That notion was quite misguided, but it was written all over my face. Gradually, however, that thinking was overlaid. I began to see that it was wrong, that it didn’t matter if I made mistakes or if my voice sounded funny, what mattered was to keep practicing. And curiously enough, people’s opinion of me began to shift, too. I’d be a better Noh artist, perhaps, if I’d had the sense to see this a decade or so earlier, mind you.

Oshima: I don’t believe that for a moment! At the same time, even in provincial Noh families like my own, the sons grow up feeling pressure to inherit the family art and I know my younger brother struggled with this. Beyond that, though, you have your standing as a branch of the Kanze family, and as a witness to the successes of your father’s generation, the mental conflict you experienced must have been immense.

Endeavoring to “translate thought into movement without reserve”

Oshima: You changed and the opinions of those around you changed too, but I wonder if you could tell us a little about your mental attitude towards what you hold to be the nucleus of your art?

Kanze: TLet me think on that for a moment. At the outset, my first thought is to make no assumptions, to perform according to the katatsuke – the stylistic movement patterns that are indicated in the manuscript. In terms of a policy, I would say that I try to perform “without reserve”. And when I perform I hold images of my uncle and my father in my head. However, since that alone could lead to misapprehensions, I ask older, more seasoned actors for their opinions and watch any video footage that’s available. Even so, it’s not possible to reenact what I see on screen, so I endeavor to translate my thoughts into movement honestly and without reserve.

Oshima: What are your relationships like with the jiutai (chorus) and the hayashi-kata (musicians), I wonder? When working as part of a team to prepare for a Noh performance, is there anything you take particular care with when chanting the jiutai, for example?

Kanze: The jiutai is a harder role to perform than the shite, I think. You have to think about the actor who is dancing, the hayashi (musical accompaniment) and the emotion of the piece as a whole. The shite wants to leave certain elements of the performance to someone and that falls to the jiutai, which makes the jiutai-kata’s role that much harder to perform. I was no match for my father. But I put that down to experience.

The jiutai need the trust of the hayashi-kata (musicians), but the strength of your breath, the veracity of the ma (pregnant/potential space) and the correctness of the words are also important. You can talk about a sense of unity, but whilst that can work there are times when the jiutai falls as its members try too hard to align their voices. In many instances, the jiutai will vary depending on the hayashi-kata, so it is better, I think, to go into a performance without making any assumptions. Even when the kōken (stage assistant) has to leave the stage to fetch something, for example, unless there are specific conventions preventing it, it is necessary to rethink every performance, I believe.

Oshima: That’s because Noh performances are living things, is it not?

I asked you just now about the utai (vocals), but when I had the opportunity to attend a practice session of Semimaru (see the Noh plays database) for Hikaru Uzawa (a female Noh actor affiliated with Tessenkai, who is apprentice to Tetsunojō Kanze IX), I felt that the directions you gave with regard to the utai showed great sensitivity and were extremely profound. I was particularly impressed by the directions you gave Hikaru with regard to her breathing. Is there anything you consider to be of particular importance to the utai, anything that you place particular emphasis upon when performing a Noh recitation?

Kanze: Semimaru is a blind, noble youth, and there are certain breathing techniques that need to be studied in order to perform the role of a blind man. In my reading, the actor (character) cannot talk carelessly and must speak without missing a sound, so restraining your breathing is only natural. But it’s not simply a matter of keeping your breath in check. Take Kagekiyo (see the Noh plays database), for example, the actors must convey the sense that they have their ears pricked, even in the midst of the boisterous action. Accordingly, in plays such as Yorobōshi (see the Noh plays database) and Semimaru, the actors must draw breath.

The part of Semimaru is one that I like for various reasons, and since the character is faced with adversity at every turn, my directions stemmed from the belief that this style of recitation is fitting, that this is the way my father performed the role.

Oshima: It’s a matter of reading into the circumstances confronting the character and/or his state of mind, is it not?

Kanze: As far as the utai is concerned, it’s a matter of ensuring that the lyrics are clearly audible. Since, however, many of the lyrics are waka (classical poetry comprising thirty-one syllables arranged in five lines of 5/7/5/7/7 syllables, respectively), it’s less about understanding the meaning of the words and more about grasping the images they convey. The actor must breathe in such a way as to communicate these images through his recitation. As Zeami wrote, it is not possible to produce festive sounds (shūgen) whilst vocalizing shades of desolation (bōoku).

In Noh circles, this is generally referred to as the voice, but I think it’s about breathing. Even plays that deal with desolation will not be a success if the jiutai (chorus) simply chant lachrymosely. The chants must be clearly audible irrespective of the delicacy of the sentiment involved. Breathing forms the basis for the voice, so it’s essential to be able to breathe correctly. Since the jiutai is a collaborative work involving several people, if the jigashira’s (the lead performer responsible for the jiutai) breathing is shallow when he chants then the other members of the jiutai will be unable to produce the correct pitch. In my opinion, Noh actors need, when they perform, to be mindful of the fact that: “Noh is uta-monogatari (a poem tale or story-in-songs) and proceeds in song”.

Both my uncle Hisao and my father observed that, since 70 percent of Noh’s success is said to lie in the utai (vocals), on no account should the utai be neglected. Be that as it may, that is not to suggest that an actor should cut corners on his kata (movements); ultimately, Noh actors must perform both the utai and the kata. (End of Part 1) ![]()

Tetsunojō Kanze performing Semimaru – “a part I love”. The fourth child of Emperor Engi, Prince Semimaru (Tsure) was born blind. Being blind, the prince is sensitive to sound, an awareness of which, says Kanze, the actor must convey through his words whilst also revealing his inherent dignity.

Kanze school shite-kata Noh actor, Tetsunojō Kanze IX (観世銕之丞)

Tetsunojō Kanze IX is the firstborn son of master Tetsunojō Kanze VIII (a Living National Treasure) and was born in Tokyo in 1956. His real name is Akeo. He learned his art from his father and his uncle, Kanze Hisao. Kanze made his stage debut at the age of four. His first performance as a shite-kata was in Iwafune (Sacred Stone Boat) at the age of eight. In 2002, he was given the ancestral name Tetsunojō Kanze IX. In 2008, Kanze was awarded the 65th Nihon Geijutsuin Shō (Japan Art Academy Award), and in 2011 also received the Shiju Hoshō (medal of honor with purple ribbon, which is awarded to individuals who have contributed to academic and artistic developments, improvements and accomplishments). As the head of the actors’ line of Tetsunojō and head of Tessenkai Theatre Company, he is expected to serve as a torchbearer for the Noh world in the years to come. He has an established reputation for the combination of strength and subtlety that he brings to his utai (vocals) and performances (interpretations). In addition to his activities in Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka, Kanze is a frequent participant in overseas performances of Noh. He has been inscribed on the list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Japan. He is representative director of Tessenkai Theatre Company (a Public Interest Incorporated Association), and president of the Nohgaku Performers’ Association (another Public Interest Incorporated Association). He is on the board of trustees of Kyoto University of Art and Design and teaches on a part-time basis at Tokyo Metropolitan High School. He is the supervising editor of the manga series “Hana Yori mo Hana no Gotoku” and the author of a work entitled “Noh no chikara – Sei to Shi wo Mitsumeru Inori no Geinō” (The Power of Noh – The performing art devoted a hard look at life and death).

Interviewer: Noh actor of the Kita school, Kinue Oshima (大島衣恵)

Uchida entered the Noh club of the Hosho School at Kyoto University and became captivated by the art there. Since Kinue Oshima is a shite actor of the Kita school. She is a member of the Nohgaku Performers’ Association. Oshima was born in Tokyo in 1974. She moved to the city of Fukuyama in Hiroshima Prefecture at the age of two, in which year she made her stage debut as a chigo (child role) in Kurama-tengu (Long-nosed Goblin in Kurama). She studied both with her grandfather Hisami Oshima (the third-generation master of the family’s Noh performers) and her father Masanobu (the fourth-generation master). In 1998, she became the first female Noh actor of the Kita school to perform on stage. She has subsequently joined a number of overseas performing tours and in 2005 was awarded the Hiroshima Prefecture Culture Award. In 2007, Oshima received the Hiroshima Prefecture Encouragement Award for Education and in 2010 was awarded the Encouragement Award for International Exchange by the Hiroshima International Cultural Foundation.