Interview

Interview

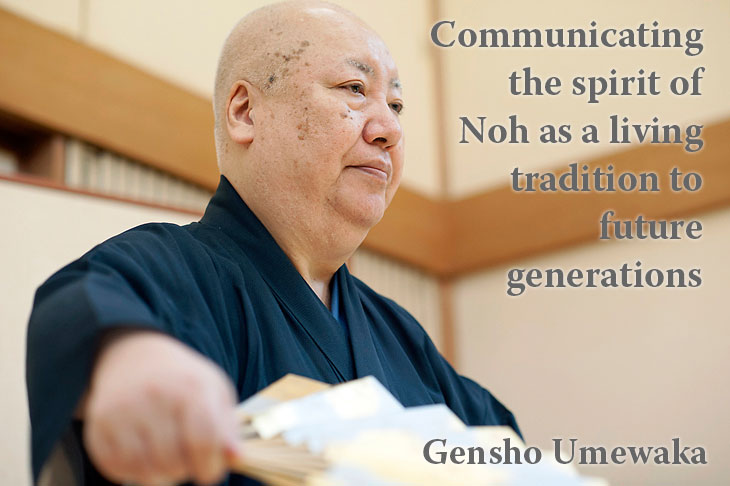

With the summer heat still lingering, I had the opportunity to interview Gensho Umewaka at his rehearsal room in Yotsuya, Tokyo. Even in the world of Noh, Gensho stands out for the sheer diversity of his efforts. I’d given my imagination free rein ahead of our encounter, but found the limitless depths of the man in person to be way beyond anything I had envisioned.

Amicable and sociable, Gensho is a fluent raconteur and I was quickly drawn into his tales. Our interview was so engrossing, in fact, that we ended up running over the allotted time. I could happily have listened to Gensho talk indefinitely, but whilst I was loath to leave it was as if I were awakening from a dream. For now, though, I must content myself with finding opportunities to see Gensho perform on various stages.

This transcript is perhaps a little too short to do our conversation justice, but I hope it conveys something of Gensho’s thoughts and his extraordinary charm. (May 18, 2015)

![]() Part 1: Continually seeking what lies at the roots of Noh

Part 1: Continually seeking what lies at the roots of Noh

Interviewer: Takahiro Uchida, the-Noh.com / Photos: Shigeyoshi Ohi

Part 1: Continually seeking what lies at the roots of Noh

Uchida: You have led a long and eventful life but do any episodes stand out as being especially memorable?

Gensho: My exchanges with the playwright, producer and theatre critic, Masaki Dōmoto, were life-changing.

Dōmoto was one of my grandfather’s disciples and in my childhood he was like an older brother to me. Dōmoto also studied under Kyutaro Hashioka IX and through his mediation, and he told me about the conversations he’d listened in on between my grandfather and Hashioka. He was my teacher, I suppose.

My exchanges with Dōmoto are what prompted me to undertake a study of the Noh plays that are in the current repertoire (genkō kyoku). It’s a subject that has kept me engrossed since I was in my thirties.

Should the current repertoire remain as it is? These plays have been passed down through multiple generations over the course of several hundred years, and this has led to misinterpretations. There’s a world of difference between performing such plays with an awareness of these errors and performances that are undertaken regardless. It doesn’t seem right to me that these mistakes should be handed mindlessly on to future generations. Given the journey Noh has taken through history, there’s an element of this that is perhaps inevitable, however. I believe that the Noh actors of the future need to take this into due consideration and assimilate it into their performances.

To address this, Dōmoto and I started meeting with a group of three or four students. These gatherings enable us to identify two or three Noh plays each year and, whilst we sometimes meet as often as two or three times a month, our ramblings and meanderings produce results. Truth be told, those ramblings are truly fascinating. Dōmoto and I are both fans of kabuki and we can talk endlessly on the subject of old kabuki actors. I’ve learned a tremendous amount from these discursions.

Uchida: It’s definitely an interesting approach. You say, for example, that the mistakes (in the current Noh repertoire) need to be understood, but could you be a little more specific as to what you intend.

Gensho: In Hagoromo (The Feather Mantle), there is a passage that is chanted “tuski no irobito” (literally, “a person as beautiful as the moon”) or “tsuki no miyabito” (literally, “a courtier of the moon”), depending on the style of the respective school. The two words – “irobito” and “miyabito” sound quite different but to my mind, it’s important for a Noh actor to understand where that difference comes from and what it means when they chant this passage.

Again, having undertaken a careful review of the rendering suggested in the time-honored Aoi no Ue (Lady Aoi) and the version of Yoroboshi (Stumbling Beggar Priest) written by one of the authors, Zeami, I find myself asking how these plays became the versions we see today. So many older versions have been chipped away over the course of time.

In times past, Yoroboshi depicted the gaiety of the neighborhood around the great Shittenoji temple in Osaka, but that revelry is missing from modern performances of the play. Nonetheless, the relationships between father and son, between people, are beautifully condensed. On the other hand, in earlier performances of the play, a single Noh actor was able to bring Yoroboshi – the blind boy, vividly to life. By combining the earlier renderings with their contemporary counterparts, it’s possible to compensate for the shortcomings of both.

Uchida: You’re speaking of differences in perspective and focus, I think. For the audience, such different points of interest are undoubtedly fascinating to watch.

Gensho: It’s not a question of one rendering being better than the other. Since its beginnings, Noh has produced almost three thousand plays of which at most 250 are in the current repertoire. That’s not a particularly large number of plays. It would be nice to see 1,000-or-so plays being performed on a regular basis, but hard on the actors needing to memorize all the different roles. That’s why I believe it’s the staging that needs to offer variation. Actors long to take on new plays, but Noh performances are a one-off event, they are a uniquely precious experience. There is a limit to the number of plays any Noh actor is capable of performing. You may perform a role and then not perform it again for another three or four years. It’s conceivable that you’ll never perform it again..

Any reflections you have after giving a single performance must thus be stored within. That’s no bad thing. Actors can draw on this store of reflections when performing other roles. That’s one of the great things about Noh.

My study of the current Noh repertoire gave me a renewed sense of the art as a one-off experience and all that that signifies, and it’s the reason why I’ve been reviving old works and creating new ones since I was in my thirties.

Uchida: I have both seen and heard about your passion for revivals and new works and it’s something that excites me no end. Would you share some of your thoughts on this topic.

Gensho: It all started back in 1983 (Showa 58), when I revived Dai-Hannya (The Sutra of Great Wisdom). It’s not part of the current Noh repertoire, and I was fascinated by the idea of creating something totally different.

I would not be able to perform either revivals or new works were it not for the combined efforts of a great many people. The assistance of Noh’s three leading actors was indispensible and I am eternally grateful. Again, the help I’ve received from my students, from the people who have been instrumental in the staging of these works, and from the many people outside the Noh world, has all been invaluable.

My aim is not to create a “Gensho World” through these explorations. This is no egotistical undertaking. I tell everyone to feel free to speak their minds, and I want the works to be co-productions, to belong to everyone involved. Though there’s no denying I can be quite headstrong.

In 1983 (Showa 58), Gensho Umewaka revived Dai-Hannya – a work that had not been performed for more than five hundred years.

According to Gensho, the catalyst for the revival was the Noh mask known as “Shinja”, which is in the Umewaka family collection and is said to have been used in Dai-Hannya. In the story, Shinja Daiou, a divinity who lives in the Ryusagawa desert, comes to the aid of Genjo Sanzo on his journey to India in search of Buddhist scriptures. Various divinities make an appearance in this colorful and fantastic spectacle.

© Umewakanohtheatre

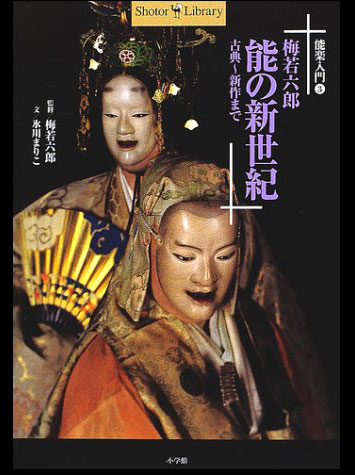

Introduction to Noh Theatre 3: Rokuro Umewaka– Noh for the New Millennium: From Japanese Classics to New Works, Shogakukan, Inc.

The book includes detailed coverage of Yume no Ukihashi (The Bridge of Dreams), Kukai (The Empty Sea) and numerous other new works created by Gensho Umewaka, as well as interviews with those involved in the making of these plays. It also contains introductions to representative Noh plays in the classical tradition, including Dojoji, and Funa Benkei (Benkei Aboard Ship). Filled with tips on how to get the most from your Noh experience, this book is a must for fans of the art.

New approaches an asset to the world of No.

Uchida: Staging both revivals and new works must be immensely challenging, but what are the rewards.

Gensho: I didn’t give this much thought when I was working on Dai-Hannya, but after reviving two or three classical plays I realized that I could incorporate the essence of traditional Noh gleaned from these revivals into performances of plays in the current repertoire. It was then that I understood how valuable was the undertaking and knew that I had no choice but to continue.

I don’t do it because it’s interesting, at least that’s not the sole reason. Reviving classical works is naturally interesting, but that element is of secondary importance. What interests me is to learn why the plays I exhume were buried by history. I believe that these plays will find a receptive audience, that there is a purpose in resurrecting them after the passage of many, many years, and that the revival of these works will facilitate a better understanding of the plays in the current Noh repertoire.

Uchida: It must be challenging, but your work is an asset to the world of Noh.

Gensho: You know the classic Noh play, Izutsu (The Well), I’m sure. For me, Izutsu is one of the finest plays in the Noh tradition. That said, I’d have difficulty articulating what it is that distinguishes this particular play. If you weren’t aware that at the time Izutsu was written it was still a rough stone – of how the play has evolved over the centuries, you wouldn’t understand what makes this play without equal today. It’s for this reason that I strive so often to revive classic Noh plays and to create new ones.

The polishing of rough stones is a fascinating process. The classical and modern versions of Izutsu are distinctly different: it was originally much closer to a shūshin mono (“devoted attachment piece” – a category of Noh plays featuring a person who suffers because of devotion to a lover). Working with Dōmoto and the other members of the group, we decided to try staging Izutsu in its classical form and produced a deep performance of the play, which, whilst it wasn’t a complete failure, provoked some hard thinking. I realized there were cogent reasons as to why Izutsu has evolved into its current form, something I wouldn’t have known had I not tried to stage it as it was originally performed.

I say to my Noh actor friends: “Let’s start by acting this out.” Actors are not like academics. It’s the live performance that counts. The students engaged in research bestow systematic knowledge and brains on us actors. We take that and transform it into live Noh performances. It’s an interesting process: the academia is important; the live performances are important; it’s a symbiotic relationship..

Uchida: Listening to your words, it seems to me that you are constantly seeking the origins of Noh, that you are engaged on a quest to find new and more engaging ways to stage this art.

Gensho: Some people think Noh is boring, don’t they.

Uchida: There are people who say it’s monotonous, yes.

Gensho: It’s a sentiment I can fully appreciate. You can’t deny that it’s a monotonous form of theater. Asking why this is so would seem to me the more pertinent question. Even Izutsu, which I consider to be exceptional, would be difficult viewing for anyone not well versed in the Noh tradition or with no background knowledge on the art.

Uchida: I imagine they’d be asleep in no time.

Gensho: Then there’s Settai (Hospitality). You’ll be familiar with that play, I’m sure.

Uchida: It’s a great play; very moving..

Gensho: In this piece, the performer appears, sits down and chants; that’s it. A friend of mine went to see Settai and told me: “It made me so drowsy, I found myself nodding off.” On asking him what happened after that, he said: “I woke up with a start only to find the same scene playing out on stage!.

But he also said that, on reflection, Noh is extraordinary. This friend is a kabuki actor and he told me that such a performance would be unthinkable in the kabuki world, that the actors would be unable to restrain themselves.

Uchida: I imagine they’d insert an action scene in there somewhere, wouldn’t they.

Gensho: He praised Noh, saying: “You lose patience, but in Noh the actors perform with complete composure. That’s what makes it so extraordinary.” Those are encouraging words: they represent an admonition that my fellow Noh actors and I would do well to heed. Noh performances contain little or no movement and yet we must find ways of drawing the audience in. As Noh actors, the question we need to be asking ourselves at this point in time is whether we have the ability to captivate audiences.

I think what’s called for is ardor, the willingness to make mistakes, to take a tumble on stage, to give it a go.

What needs to be passed on to the next generation of Noh actors? What will Gensho Umewaka’s legacy be.

Uchida: Your words remind me of just how extraordinary the Noh tradition is. What are your thoughts on handing this remarkable performance art onto future generations?.

Gensho: Each of the Noh School styles has its traditions; the difficulty lies in identifying what these traditions are. To be more specific, each school style advocates different methods of chanting and dance. Nonetheless, these may have evolved through imitation of the virtuoso performances of Noh masters in bygone ages. This is actually a major element.

The Umekawa school of Noh, for example, is known for the flamboyance and beauty of its chants, but this is something that has been passed down through many generations. It’s not a so-called “Umewaka style”, it’s classic Kanze style. In point of fact, I am the fourth generation head of the Umewaka family. Minoru Umewaka, the first, was, to put it plainly, an amateur. But he worked incredibly hard and became one of the three Noh masters of the Meiji era (1868-1912) alongside Kuro-Tomoharu Hosho and Banma Sakurama.

But my great-grandfather, on the other hand, studied under a master of the Kanze School, and it was his style that, somewhere along the line, became characteristic of the Umewaka family. A stranger, someone with no connection to the Umewaka family, once visited our home and, upon hearing an Umewaka chant said that it “brought back fond memories.” Asked why, he said it reminded him of the classic Kanze style.

The dance and chanting traditions have been interrupted and some have emerged over the course of Noh’s history. What I hope to pass on, therefore, is the Noh ethos: its soul as opposed to its form. This is what has been handed down through successive generations of school style. Viewed from a broader perspective, it becomes clear that style is also irrelevant. It’s the soul of Noh that is being handed on, and it is for precisely this reason that, as inheritors of the Noh tradition, we need to unravel the whys and wherefores of Noh today, to understand why it has come to be performed as it is now.

Uchida: This relates back to your words on the rewards of taking up the challenge of revivals and new works, I think.

Gensho: Izutsu has been stripped down over time to its current form. It’s important to give thought to the souls of the many Noh actors who have polished its rough stones during this pruning process.

There’s little sense in assuming airs and pronouncing: “This is Noh”, having simply seen the jewel that is today’s finely honed version of Izutsu. You need to think about the ways in which this play was refined over time. This thinking process is what I believe needs to be passed on for all those involved in Noh.

Uchida: You’re speaking of Noh as a living tradition, aren’t you? Something that needs to be kept alive through the efforts of its performers.

Gensho: Yes. Noh is not a written art form. You’d be in all kinds of trouble if you made the mistake of reading Fushi Kaden (the treaty on Noh written by Zeami, one of the great masters). People have said a whole host of things to me having read Zeami, but I respond simply by telling them: “You’re not Zeami, are you?” Asked, during a conversation with Masako Shirasu, as to whether he’d read Fushi Kaden, my grandfather said: “We had a book like that at home, but I was told not to read it until I’d honed my own performances”.

Many of the passages in Fushi Kaden were written after Zeami had achieved great success. I’m not saying that it’s wrong to read this work. But I simply suggest that you need to be wary of being drawn too closely in; i.e. believing in the misguided notion that you should strive to exactly become the state Zeami suggested.

Uchida: You believe that it would be hazardous were Zeami’s words to become the golden rule, then.

Gensho: Tradition in that form is frightening. We are blessed to have a number of classical Noh texts in our library. They need to be read with a grain of salt, I think: you need to ask yourself whether it’s sensible to believe every word on the page. The experience of reading these texts has changed for me over time, too. Now I find myself questioning what I read. Conversely, in my younger days I genuinely believed I’d discovered the essence of Noh.

Uchida: So, it’s taking all this into account that makes Noh a living tradition.

Gensho: Right. Traditions must live if they are to survive. This is what we in the Noh world need to be contemplating as we go about our daily lives.

Noh needs magnetic, self-assertive actors!

Uchida: What would you like to communicate to your successors.

Gensho: Efforts to broaden the reach of Noh are essential. The difficulty lies in finding ways to accomplish that end, of enhancing the magnetism of important actors. We need to produce interesting actors. By interesting I don’t mean fun loving. We need, I think, to be cultivating actors that give audiences a sense of the myriad possibilities of Noh.

Uchida: Not an actor who is simply appealing because he is adept at the kata (the stylistic movement patterns that form the gestural vocabulary and blocking of the dance) and chants beautifully; but an actor who presents audiences with more depth, an actor who is unpredictable, who excites people. Is that what you mean.

Gensho: Exactly. I’m speaking of actors who can elevate their performances to a higher level, and we need to ensure that we don’t get in the way of these rising stars. It’s an all-too-common phenomenon in our world. When things start going wrong, they’ll continue to go wrong even without any adverse interference. What we need to be doing, then, is to give rising actors a boost.

We need to be promoting actors in whom we recognize potential. Talented actors can go far with a little sustained effort, but they will fall by the wayside unless they work hard. An actor’s success is his own making.

In terms of enhancing Noh’s popularity, I think we need to be planning gala events that are guaranteed to draw audiences. But before that, our task is to create an environment that will allow Noh actors to gain experience and hone their skills. That’s our responsibility as elders and mentors. Some actors view suggestions to try something new as a form of impudence, but I love brashness. Actors should be brash, though brashness alone is not enough, of course.

Uchida: And therein lies the rub; am I right.

Gensho: A combination of self-assertiveness and effort is essential if an actor is to succeed in winning over the rest of the Noh world. First and foremost, we need to be breeding actors who are prepared to work; that’s the key to revitalizing Noh.

Uchida: There are various ways to go about staging an event, but raising new actors is a whole different ball game, isn’t it.

Gensho: It’s incredibly difficult, but if we fail to cultivate new actors the Noh tradition could die out; it’s that serious.

The Meiji Restoration led to the disappearance of Noh during my great-grandfather’s lifetime. I imagine it was that that drove him to become a great actor. There would have been little sense in staging dull, uninteresting plays now, would there? I believe this is why my great-grandfather rose to such great heights from being an amateur.

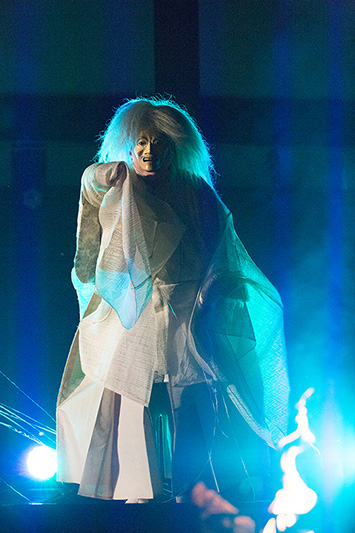

The JAKMAK Suite: a collaboration between Gensho Umewaka and violinist Taro Hakase. JAKMAK was premiered at Kamogama Shrine in Kyoto, on Saturday, May 24, 2014, as part of festivities to mark the transfer of the deity to a new shrine building next year.

Photograph: © Ikuhara Yoshiyuki

The second movement:“A Memory”, expresses the melancholy of human life. The fourth movement:“Pray”, brought the event to a climax as Gensho recited a self-authored chant in modern Japanese to an improvised accompaniment performed by Hakase and the dance questioned the meaning of life.

Photograph: ©Ikuhara Yoshiyuki

Uchida: On the subject of Meiji, last winter you performed Semimaru (Prince Semimaru) with the head of the Hosho School (Kazufusa Hosho) at an event entitled “The Year of Meiji 8 (1875) – Dawn of Nohgaku” that was presented by the Yokohama Noh Theater; Semimaru being a play that was performed in 1875 by Kuro Hosho and Minoru Umewaka.

Gensho: Kuro Hosho did a great service to the Umewaka family during the Meiji Era. We are greatly indebted to him. In that sense, I was extremely happy to be given the opportunity to perform with Kazufusa Hosho at the end of last year.

That we are now in an age when it’s possible to mount an event in which the head of the Kanze School and the head of the Hosho School perform together is a source of enormous pleasure to me, too. I felt the energy of the younger generations and it gave me encouragement. Older actors may have much to say on the matter, but I think we can safely ignore that.

At the same time, the schools and patriarchal system need to stay. The patriarchal system, in particular, since it is ideally suited to the world of Noh. I think it’s important to preserve these formal elements..

I often say: “Actors who are protected by their families should sound the change”. Defense is a form of attack, after all. Noh needs both. The existence of schools and Noh families is what allows us to safeguard the form. Beyond that, individual actors must combine forces and launch an offensive. Once that happens the world of Noh will become more interesting, I think, though I’m just a bystander now.

Uchida: Not at all! Young actors are splendid, but I continue to expect great things from you. I’m astounded at the many innovative, interesting endeavors you undertake; your collaboration with violinist Taro Hakase at Kamogamo Shrine in Kyoto last year (at JAKMAK in May 2014, an event that was broadcast on BS Asahi in July), for example.

Gensho: That collaboration came to fruition thanks to the efforts of producer Tomoko Nishio. In my belief, Noh actors need to be actively performing with people from outside the world of Noh. (End of Part 1) ![]()

Gensho Umewaka (梅若玄祥), a principal actor of the Kanze School and current head of the Umewaka family

Born 1948 (Showa 23), Gensho made his first stage appearance as a child in 1951 (Showa 26) in Kurama-Tengu. Gensho assumed the name of Rokuro Umewaka LVI in 1988 (Showa 63); changing his name to Gensho Umewaka II in 2008 (Heisei 20).

Today he is a popular and accomplished lead actor. Gensho works actively to revive near-forgotten works and stage unique new ones, and his willingness to attempt different staging styles is helping to keep the classical Noh tradition alive and well. He is eager to introduce Noh to foreign audiences and besides staging the first international exhibition of Noh masks and costumes, has performed in America, France, the Netherlands and Russia. He is one of the pioneers in the effort to bring Noh to auditoriums. He is admired both inside and outside the world of Noh and by artists the world over as one of the rare individuals who looks upon every meeting as a fortuitous event. Gensho has been designated an Important Intangible Cultural Property of Japan and is on the executive board of The Japan Art Academy, Association for Japanese Noh Plays, and the Japan Theater Arts Association. He is president of the Umewaka Noh Theater Association and director of the Umewaka Noh Theater, and is representative of the Noh project “Koroku”.

Interviewer: Takahiro Uchida (内田高洋), the-Noh.com

Uchida entered the Noh club of the Hosho School at Kyoto University and became captivated by the art there. Since then, watching plays and learning about all aspects of Noh, he has practiced singing and dancing with the Hosho School as well as playing fue (flute) at the Morita School and taiko (stick drum) at the Kadono School. He also writes and edits the Hosho newsletter of the Hosho School.